ATTORNEY GRIEVANCE COMM'N v. BERRY

Issue: What sanction should the Court impose upon an attorney who repeatedly took Estate money without authorization and concealed these disbursements over a seven year period in 12 separate filings?

Holding: Having violated Maryland Lawyers' Rules of Professional Conduct 1.15(a), 3.3(a)(1), 8.4(b) and (d) with dishonest conduct, over a seven year period, in twelve separate filings, the attorney's theft of Estate funds warranted disbarment.

Alleged Violations: Maryland Lawyers' Rules of Professional Conduct 3.3(a)(1) (Candor Toward the Tribunal); 8.4(b), (c) and (d) (Misconduct); and Rule 1.15(a) (Safekeeping Property); concomitant with violations of Section 10-306 of the Business Occupations and Professions Article, Maryland Code (Misuse of Trust Money); Section 10-606(b) of the Business Occupations and Professions Article, Maryland Code (Penalties);Maryland Rule 16-607 (Commingling of Funds); and Maryland Rule 16-609 (Prohibited Transactions).

Citation: 437 Md. 152, 85 A.3d 207 (2014)

Opinion

PANEL: BARBERA, C.J., HARRELL, BATTAGLIA, GREENEL, ADKINS, McDONALD, WATTS, JJ.

Opinion by BATTAGLIA, J.

Gene Berry, Respondent, was admitted to the Bar of this Court on December 15, 1988. On November 26, 2012, the Attorney Grievance Commission, acting through Bar Counsel ("Bar Counsel"), pursuant to Maryland Rule 16-751(a),[1] filed a "Petition For Disciplinary or Remedial Action" against Berry, charging violations of the Maryland Lawyers' Rules of Professional Conduct, including Rules 3.3(a)(1) (Candor Toward the Tribunal),[2] 8.4(b), (c) and (d) (Misconduct),[3] and Rule 1.15(a) (Safekeeping Page 2 Property),[4] concomitant with violations of Section 10-306 of the Business Occupations and Professions Article, Maryland Code (2000, 2010 Repl. Vol.) (Misuse of Trust Money),[5] Section 10-606(b) of the Business Occupations and Professions Article, Maryland Code (2000, 2010 Repl. Vol.) (Penalties),[6] Maryland Rule 16-607 (Commingling of Funds),[7] and Page 3 Maryland Rule 16-609 (Prohibited Transactions).[8] Bar Counsel alleged in its Petition for Disciplinary or Remedial Action that after Berry's assumption of the duties of successor personal representative for the Estate of Patricia Mae Bowles ("Bowles Estate"), Berry withdrew more than $50,000 without court authority, deposited his own funds into the Bowles Estate account to cover deficiencies, and submitted multiple accounts to the Orphans' Court containing false statements and misrepresentations to conceal unauthorized withdrawals from the Bowles Estate account. Page 4 Additionally, Bar Counsel alleged that Berry failed to hold and maintain the funds of clients in trust, while depositing his own funds in his attorney trust account to cover overdrafts, as well as using client funds to reimburse other clients. In an Order dated December 4, 2012, this Court referred the matter to Judge Steven G. Salant of the Circuit Court for Montgomery County for a hearing, pursuant to Rule 16-757.[9] Judge Salant issued Findings of Fact and Page 5 Conclusions of Law, after which this Court held oral argument. Immediately following argument, a Per Curiam Order disbarring Berry was entered on January 14, 2014, which stated:

ORDERED, by the Court of Appeals of Maryland, that the respondent, Steven Gene Berry, be, and he is hereby, disbarred, effective immediately, from the further practice of law in the State of Maryland; and it is furtherORDERED that the Clerk of this Court shall strike the name of Steven Gene Berry from the register of attorneys, and pursuant to Maryland Rule 16-760(e), shall certify that fact to the Trustees of the Client Protection Fund and the clerks of all judicial tribunals in the State; and it is further

ORDERED that respondent shall pay all costs as taxed by the Clerk of this Court, including the costs of all transcripts, pursuant to Maryland Rule 16-761(b), for which sum judgment is entered in favor of the Attorney Grievance Commission of Maryland against Steven Gene Berry.

Judge Salant's written Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law stated:

Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law[10]Pursuant to an Order of the Court of Appeals dated December 4, 2012, the above-captioned disciplinary matter was transmitted to the Circuit Court for Montgomery County, Maryland, for trial Page 6relating to Respondent's alleged professional misconduct in misappropriating funds in an estate escrow account as successor personal representative and attorney for the estate and for overdrafting funds in his attorney trust account. The matter came before this Court for a two-day trial on April 15, 2013. Upon consideration of the evidence presented at trial and the arguments of counsel and the parties, this Court finds the following facts to have been established by clear and convincing evidence:

Findings of Fact

Background

Respondent, Steven Gene Berry ("Respondent" or "Berry") was admitted to the Maryland Bar on December 15, 1988. Berry has also been previously admitted to the Oregon Bar (1978) and the Indiana Bar (1982). Respondent operates a general solo practice in Bethesda, Maryland that consists primarily of representing individuals with small traffic or criminal matters in the District Courts of Maryland, occasional trust and estate work, occasional domestic relations cases, relatively simple wills and powers of attorney, and some court-appointed federal misdemeanor and appellate cases. Respondent has no associates, secretary, receptionist, law clerk, or paralegal. Respondent has no previous history of bar complaints or disciplinary actions.

The Bowles Estate

On February 15, 2005, Respondent was appointed as successor personal representative in the Estate of Patricia Mae Bowles ("Bowles Estate"), Estate No. W-43773, in the Orphans' Court for Montgomery County. Respondent was appointed to this position after the original personal representative, Michelle B. Allen, misappropriated more than $300,000 from the Bowles Estate. On May 12, 2005, Respondent opened an escrow account for the Bowles Estate at Mercantile Potomac Bank (now PNC Bank) titled "Estate of Patricia Mae Bowles, Steven G. Berry (Personal Representative)" ("Bowles escrow account"). Respondent opened the account with a check in the amount of $14,997.66 from Wachovia Bank, where the Bowles escrow account was originally held by Michelle Allen.

John DeBone, a paralegal with the Attorney Grievance Commission, reviewed, summarized, and analyzed Respondent'sPage 7 bank records and accounts submitted to the court. As DeBone testified, Respondent's accountings contained three types of errors: (1) a check went through the bank but the check listed on the accounting was listed as a different amount; (2) a check went through the bank but was never listed on an accounting; and (3) a check listed on the accounting never went through the bank during the time period reviewed.

Throughout his appointment as successor personal representative and attorney to the Bowles Estate, Respondent made numerous unauthorized disbursements to himself for commission and attorney's fees and failed to accurately reflect these disbursements on his accounts to the court. On November 4, 2005, Respondent wrote Check Number 1003 payable to "Steven G. Berry" as "Successor Personal Representative" in the amount of $9,500 from the Bowles escrow account, and cashed the same on November 7, 2005. On November 18, 2005, Respondent wrote Check Number 1004, again payable to himself, in the amount of $4,500, and cashed the same on November 21, 2005. On December 2, 2005, Respondent wrote Check Number 1005, payable to himself in the amount of $500, and cashed the same on December 5, 2005. At the time Respondent withdrew funds for himself in the total amount of $14,500 from the Bowles escrow account, he had not received approval from the Orphans' Court to disburse monies to himself as successor personal representative, nor did he petition the court for approval to disburse despite being aware that he was required to do so. Respondent also had not received consent from the interested persons of the Bowles Estate to disburse monies to himself for personal representative commission or counsel's fees.

On December 6, 2005, after having already disbursed a total of $14,500 to himself, Respondent filed a Petition for Allowance of Interim Personal Representative Commission and Interim Attorney's Fees ("First Petition") requesting an interim personal representative's commission and counsel's fee of $15,834.37 for services he rendered on behalf of the estate and stating that he applied a 25% professional courtesy discount to the actual time expended on the case. In the Petition, Respondent falsely represented that the Bowles escrow account had a "sum total of $22,671.44." In fact, as of December 5, 2005, when Respondent served the Petition upon interested parties, there was Page 8a balance of $8,171.44. The balance was $8,171.44 as a result of disbursements Respondent made to himself totaling $14,500, which Respondent failed to disclose to the Court in the First Petition. On January 17, 2006, the Court approved Respondent's request for $15,834.37 as and for commission and fees.

Seven months later, on July 17, 2006, Respondent filed his First Account of Successor Personal Representative for the period of January 11, 2004 through July 17, 2006. Berry signed the First Account under oath and under the penalties of perjury. However, Respondent knowingly and deliberately presented inaccurate information in his First Account to give the false impression that his accounting and disbursements of monies held in the Bowles escrow account were proper and lawful. In his First Account, Respondent represented that Check Number 1003 was dated 5/24/2005, was in the amount of $21.18, and was issued to "U.S. Postal Service" for "payment for certified mail postage." However, Check Number 1003 was actually dated 11/4/2005, was in the amount of $9,500, and was issued to "Steven G. Berry" for "Patricia M. Bowles." Also, Respondent excluded a copy of Check Number 1003 from his First Account, although he included copies of most of the other checks he disbursed from the Bowles escrow account.

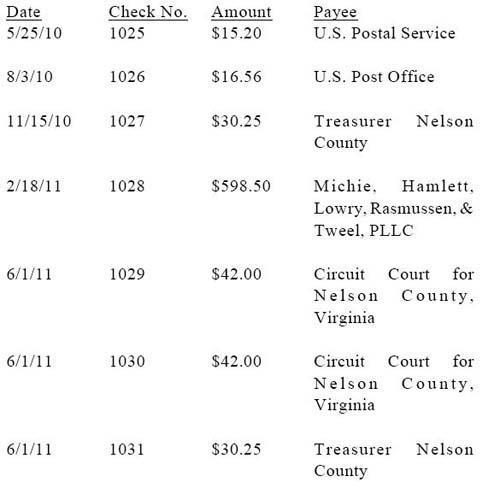

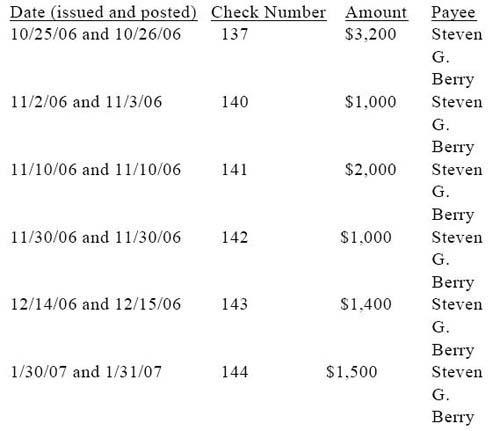

In addition to misrepresenting Check Number 1003 in his First Account, Respondent failed to disclose numerous checks that he issued to himself from January 11, 2004 to July 17, 2006 without authorization or approval from the Orphans' Court, as follows:

In sum, by July 2006, Respondent had taken for himself a total of $31,750 from the Bowles escrow account without authorization from the court and without disclosing same to either the Orphans' Court or to the interested persons.

In his First Account, Respondent additionally misrepresented that he disbursed Check Number 115, dated 1/21/2006, for the amount of $15,834.37 to Steven Gene Berry as "personal representative's commission and counsel fee." However, Respondent never presented that check for payment. Respondent admitted during trial that he never intended to cash the check, but only wrote it and presented a copy to the court to give the false impression that he did. Respondent knew that such information was false and inaccurate, yet included the same to purposefully conceal the multiple unauthorized payments to himself.

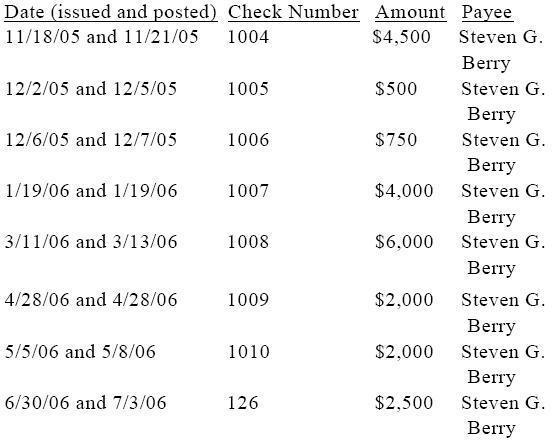

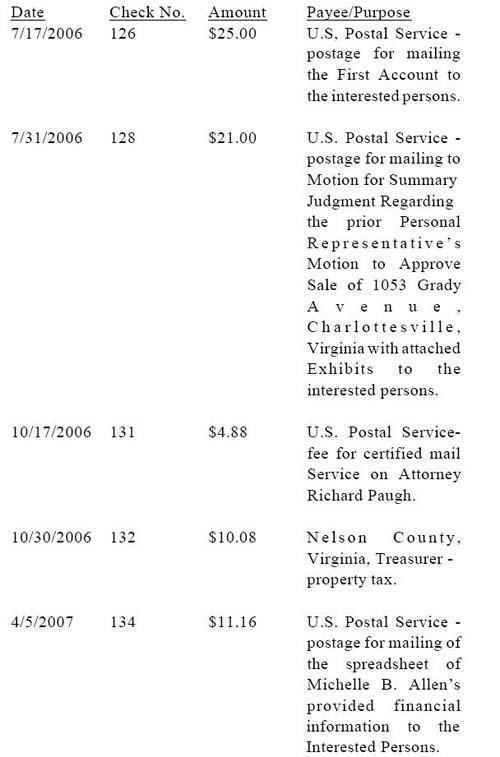

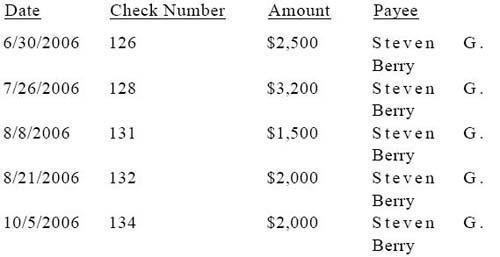

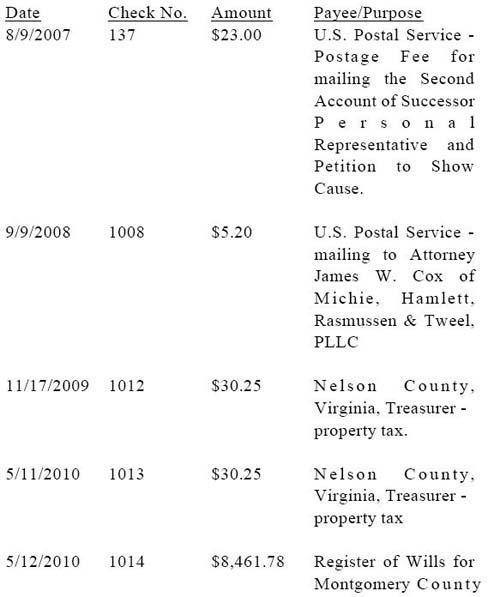

Respondent subsequently filed eight additional accounts, all signed under oath and penalties of perjury, and all of which contained misrepresentations and omissions. On July 31, 2006, Respondent filed an Amended First Account of Successor Personal Representative of the Bowles Estate in which he continued to make the same misrepresentations as he did in his First Account. On July 10, 2007, Respondent filed his Second Account of Successor Personal Representative. Not only did the Second Account contain the same misrepresentations from his previous account but also contained additional misrepresentations to conceal the unauthorized disbursements to himself from the Bowles escrow account. Respondent fabricated the dates, amounts, and payees on checks, as well as the purpose of the disbursements of the checks. Respondent provided, in part, the following in his Second Account:

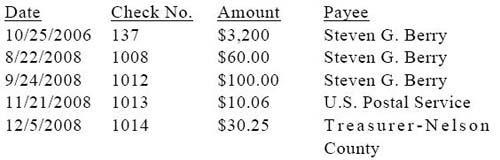

The actual disbursements Respondent made for these check numbers, as revealed by the bank records of the Bowles escrow account, were as follows:

Respondent never disclosed the actual disbursements to the Court or to the interested persons of the Bowles Estate. In addition, as Respondent had done in the First Account, Respondent failed to disclose in the Second Account the following checks that he issued to himself from the Bowles escrow account:

By July 2007, Respondent had taken a total of $50,550 from the Bowles escrow account without authority or approval from the court.Page 12

From April 30, 2008 through May 20, 2010, Respondent filed his Third, Fourth, Fifth and Amended Fifth Accounts of Successor Personal Representative, which, again, were prepared and filed under oath and under penalties of perjury. These accounts not only contained the same misrepresentations and omissions from Respondent's previous accounts, but also contained additional misrepresentations concerning disbursements he made to himself from the Bowles escrow account. Respondent again fabricated the dates, amounts, payees, and purposes of the disbursements. For example, Respondent provided, in part, the following in his Third, Fourth, Fifth, and Amended Fifth Accounts:

The actual disbursements Respondent made for these check numbers, as revealed by the bank records of the Bowles escrow account, were as follows:

Respondent never disclosed the actual disbursements of these checks to the Court or to the interested persons of the Bowles Estate. Further, Respondent never corrected any of his accounts with the Orphans' Court as to either his omissions or misrepresentations.

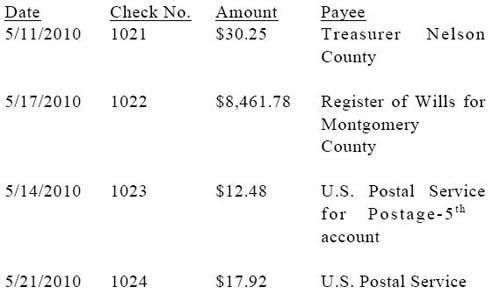

As of May 1, 2010, the balance of the Bowles escrow account had been reduced to $834.95 after Respondent had made multiple unauthorized payments to himself. On May 12, 2010, despite this reduced account balance, Respondent issued Check Number 1022 in the amount of $8,461.78 to "Register of Wills for Montgomery County," when the Bowles escrow account did not contain sufficient funds to cover the check. In order to cover the shortfall, on May 11, 2010 and May 13, 2010, Respondent's father, Donald Berry, wired $5,000 and $3,000, respectively, into Respondent's Attorney Trust Account. On May 12, 2010 and May 14, 2010, Respondent deposited nearly all of the monies he received from his father, specifically $4,900 and $2,900, respectively, into the Bowles escrow account. But for the monies from his father's loan, Respondent would not have had sufficient funds in the Bowles escrow account to cover the entire amount of Check Number 1022. Respondent purposefully deposited his own personal funds into the Bowles escrow account to cover the deficiency caused by his unauthorized payments to himself from the escrow account.

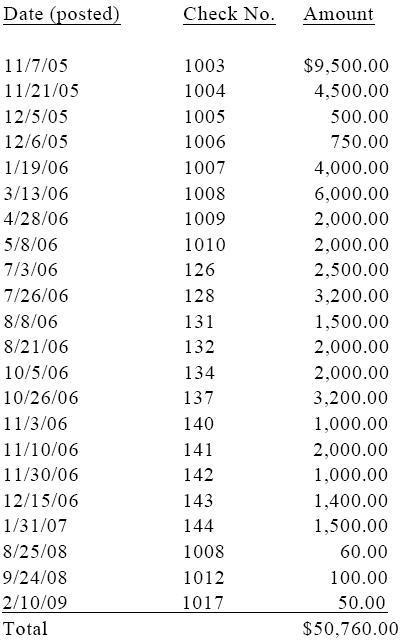

On August 3, 2010, Respondent filed his Amended Petition for Second Interim Personal Representative Commission Page 14and Attorney Fees ("Second Petition"), which was signed under oath, requesting an additional $23,828.06 in commission and attorney's fees. Respondent attached his invoice for work allegedly performed on behalf of the Bowles Estate from December 9, 2005 through May 20, 2010 and indicated that had he charged his normal fee rate, he would have generated a fee of $69,919.50. However, when Respondent filed the Second Petition, only $80.76 remained in the Bowles escrow account because Respondent has already taken for himself a total of $50,760 without any authority or approval from the court. Respondent failed to disclose the disbursements he made to himself from the Bowles escrow account. Respondent falsely represented that the Bowles estate had a "balance forward of $24,534.56" and that it was "SOLVENT".

On January 14, 2011, the Orphans' Court granted Respondent's Second Petition and authorized Respondent to pay himself $23,828.06 from the assets of the Bowles Estate. Based upon the two Orders granting Respondent's requests for interim commission and fees, Respondent was authorized by the Court to pay himself a total of $39,662.43 from the assets of the Bowles Estate. Significantly, as of February 10, 2009, Respondent had already paid himself, without any notice to or authority from the court, a total of $50,760 from the Bowles escrow account as follows:

In January 2011, the Bowles escrow account balance fell to $50.51, which was insufficient to cover the remaining checks issued by Respondent to complete the administration of the Estate. Therefore, on January 24, 2011, Respondent again deposited his personal funds in the Bowles escrow account in the amount of $664.99 to cover additional checks he had disbursed on behalf of the estate.

As previously noted, Respondent took $50,760 from the Bowles Estate at a time he was only authorized by the Court to take $15,834.37. Respondent, therefore, unlawfully took $34,925.63 in commission and fees from the Bowles Estate and never disclosed the same to the Orphans' Court. Even considering the Court's approval of an additional $23,828.06 in commission and fees based on Respondent's Second Petition, for a total amount approved of $39,662.43, Respondent still unlawfully took $11,097.57 in commission and fees from the Bowles Estate over what was approved by the Court without ever revealing the same.

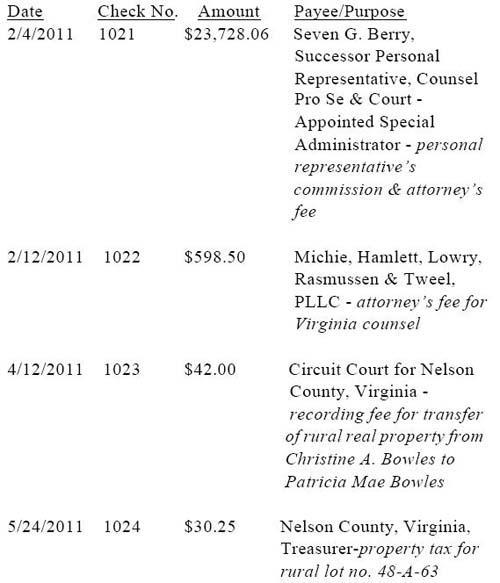

On August 1, 2011, Respondent filed his Sixth Account of Successor Personal Representative for the period from May 14, 2010 through July 31, 2011. In his Sixth Account, Respondent continued to make the same misrepresentations as in his previous accounts, as well as new misrepresentations as follows:

However, the actual disbursements Respondent made, as revealed by the bank records of the Bowles escrow account, were as follows:

Respondent never disclosed the actual disbursements to the Court or to the interested persons of the Bowles Estate. Respondent deliberately and purposefully misrepresented the amount and payee of Check Number 1021 to give the court the false impression that he was making proper and authorized disbursements to himself from the Bowles Estate, when, in fact, he had taken above and beyond what the court had authorized to pay himself as commission and attorney's fees. Respondent failed to disclose in his Sixth Account the following checks that he issued from the Bowles escrow account:

By February 2012, Respondent received notice that Bar Counsel was investigating his disbursements as successor personal representative and attorney of the Bowles Estate. However, on March 12, 2012, Respondent filed, under oath, his Third and Final Petition for Allowance of Successor and Personal Page 18Representative Commission and Attorney's Fees ("Third Petition") and failed to disclose to the court disbursements he made to himself. In his Third Petition, Respondent requested an additional $26,492.70 in commission and fees, and further requested, in light of the estate being insolvent, that the original personal representative's bond be condemned and applied to his outstanding commission and fees. Nowhere in his Third Petition did Respondent mention that as of February 2009, he had taken $11,097.57 more than he was authorized by the Court to take as commission and fees. Rather, Respondent falsely claimed that he incurred expenses "which were paid out of the undersigned's own funds in order to carry this matter through to a conclusion and which are not requested herein simply as a matter of convenience. . . ." In fact, Respondent never used his own funds in the Bowles Estate matter, but rather used funds from his escrow account, making payments to himself approximately nineteen times between 2005 and 2007, without any notice, approval or authorization from the court. On April 24, 2012, the court authorized Respondent to pay himself a total of $26,492.70 in commission and fees. On the same day, the court also approved Respondent's request that his commission as personal representative of the Bowles Estate be taxed as court costs against the estate so that Respondent could be paid out of the original personal representative's $18,000 bond. Accordingly, on July 6, 2012, Respondent was paid an additional $18,000 by the bond from Travelers Casualty and Surety Company of America.

With the court's approval of his Third Petition, Respondent was authorized to pay himself a total of $66,155.13 ($15,834.37 + $23,828.06 + $26,492.70) in commission and fees. However, Respondent actually paid himself a total of $68,760 ($50,760 + $18,000). Thus, even with the court's approval of his Third Petition, Respondent took $2,604.87 more than the Court authorized.

Bar Counsel Investigation and Overdraft of Attorney Trust Account

On July 20, 2011, Bar Counsel received an overdraft notice dated July 15, 2011 from United Bank concerning Respondent's Attorney Trust Account. The notice reported that Check Number 1106 in the amount of $125 to Sean Murphy was presented for payment on June 24, 2011 and because there was Page 19insufficient funds at the time of presentation, there was an overdraft on the trust account in the amount of (negative) -$141.27. On July 21, 2011, Assistant Bar Counsel, Dolores O. Ridgell, sent a letter to Respondent requesting his written explanation of the overdraft notice, along with copies of his client ledgers, deposit slips, canceled checks, and monthly bank statements "for the period April 2011 to the present."

On July 30, 2011, Respondent sent a letter in response to Ms. Ridgell's letter of July 21, 2011, attaching copies of his monthly bank statements, checks, and deposit slips. Respondent stated that upon discovering the overdraft in the account, he immediately drafted a check from his office account in the amount of $175.00, which posted to the escrow account the following business day, June 27, 2011, and that no client was adversely affected. Respondent's letter did not include copies of his client ledgers. Therefore, on August 9, 2011, Bar Counsel, Glenn M. Grossman, sent a letter requesting copies of Respondent's client ledgers for March through June 2011. Subsequently, on August 18, 2011, Respondent sent a letter to Bar Counsel, attaching copies of check stubs, an account ledger with running balances, and client ledgers. Respondent's own check ledgers represent that on multiple occasions, Respondent maintained a negative balance in his Attorney Trust Account. Consequently, in September 2011, Bar Counsel informed Respondent that the matter should be docketed and an investigation would be conducted. On September 27, 2011, Bar Counsel served upon United Bank a subpoena commanding the bank to produce Respondent's Attorney Trust Account records for the time period "January 1, 2010 to the present."

The bank records of Respondent's Attorney Trust Account clearly show that from January 2010 to September 2011, Respondent failed to hold and maintain client funds in the client's trust account. During the same time period, Respondent also used certain clients' funds to pay for other clients' matters. Additionally, Respondent's client ledgers contained false representations as to withdrawals and deposits regarding his clients' escrow accounts.

Respondent had a contingency fee agreement with his client Lobsang Wangkang in which Respondent was to receive one-third of any settlement he recovered on behalf of the client.Page 20

On May 18, 2011, Respondent deposited settlement proceeds of $400 in his Attorney Trust Account on behalf of Wangkang. On June 16, 2011, Respondent disbursed $266.67, two-thirds of the settlement amount, to Wangkang. Although Defendant's client ledger lists a disbursement of $133.33 for attorney's fees to the Respondent (one-third of the settlement proceeds), Respondent's bank records evidence that this disbursement was never actually made. On June 24, 2011, Respondent disbursed Check Number 1006 in the amount of $125 on behalf of Wangkang to Sean Murphy, a process server, leaving only $8.33 remaining in Wangkang's escrow account ($400-$266.67-$125 = $8.33). However, on August 23, 2011, Respondent disbursed another check (Check Number 1120) to Wangkang in the amount of $266.67, using funds deposited in his Attorney Trust Account on behalf of clients Adi ($200) and Haas ($500). But for the two deposits on behalf of Adi and Haas, Respondent would not have been able to pay Wankang on August 23, 2011.

On February 9, 2012, John DeBone met with Respondent and his attorney, Gary A. Stein, Esquire, at Respondent's office to review Respondent's trust account and client ledgers. After the meeting, Respondent gave Mr. DeBone, per his request, documents related to the Bowles Estate and to Respondent's other clients, namely: Lobsang Wangkang, Sharon Strand, Lyuba A. Varticovski, Marcos R. Ardon, Maria E. Parra, including client ledgers and invoices in relation to Respondent's representation of said clients. Respondent's client ledgers, invoices, and Attorney Trust Account records showed that Respondent withdrew his fees that he deposited into his trust account prior to earning same. The documents further showed that Respondent made inaccurate entries in his client ledgers which gave the false impression that he was maintaining an accurate accounting of his client funds.

In the case of Strand, Respondent represented in his client ledger that he received from Strand $750 on January 29, 2011 and that he withdrew $750 for attorney's fees on February 14, 2011. However, the bank records reviewed by John DeBone, dating from January 2010 through August 2011, show that no withdrawals were made on behalf of Strand by Respondent on February 14, 2011 or at any time during this period. Notably, Respondent's invoice for Strand stated that on January 31, 2011, Page 21he earned $141 to review case materials and to prepare the case file, leaving an unearned trust balance of $609 ($750 - $141) to be maintained in his Attorney Trust Account on behalf of Strand. However, as of February 1, 2011, the Respondent maintained a total Attorney Trust Account balance of only $480.17, an amount below that required to be maintained on behalf of Strand.

Similar misrepresentations were made by Respondent in his client ledgers for Varticovski, Ardon, and Parra. In all three cases, Respondent stated that certain amounts were received and disbursed in his client ledgers, when, in fact, they were not. At trial, Respondent testified that these contemporaneous client ledgers, which he submitted to bar counsel, and which indicate that he withdrew funds from the escrow account as and for attorney's fees, were in fact false. Also, in all three cases, Respondent failed to maintain and hold in trust unearned fees in his Attorney Trust Account on behalf of Varticovski, Ardon, and Parra.

Conclusions of Law

Respondent has been charged with violating Maryland Rules of Professional Conduct 1.15, 3.3, and 8.4. This Court finds that Respondent violated Maryland Rules of Professional Conduct 1.15(a), 3.3(a)(1), and 8.4(a), 8.4(c), and 8.4(d).

It is undisputed that Respondent misappropriated funds belonging to the Bowles Estate. There is no dispute that Respondent took over $34,000 in personal representative commission and attorney's fees without authority from the court or consent of interested parties. It is also undisputed that in all nine accounts that Respondent signed under oath and submitted to the court, Respondent knowingly fabricated or omitted information, including wrong dates, check numbers, amounts on checks, names of payees, and descriptions of payments from the Bowles estate account, failing to disclose all the disbursements he made to himself from the Bowles escrow account. Finally, it is undisputed that Respondent failed to hold and maintain in trust funds of clients at all times from January 2010 through September 2011, and Respondent used other clients' funds to pay certain other clients.Page 22

MRPC 1.15; Md. Rule 16-609; Md. Bus. Occ. & Prof. Code Ann. § 10-306

(Safekeeping Property and Misuse of Trust Money)

MRPC Rule 1.15(a) provides in part:

(a) A lawyer shall hold property of clients or third persons that is in a lawyer's possession in connection with a representation separate from the lawyer's own property. Funds shall be kept in a separate account maintained pursuant to Title 16, Chapter 600 of the Maryland Rules. Other property shall be identified specifically as such and appropriately safeguarded, and records of its receipt and distribution shall be created and maintained. . . .

MRPC Rule 1.15(c) provides:

(c) Unless the client gives informed consent, confirmed in writing, to a different arrangement, a lawyer shall deposit legal fees and expenses that have been paid in advance into a client trust account and may withdraw those funds for the lawyer's own benefit only as fees are earned or expenses incurred.

Attorney Trust Account

There is clear and convincing evidence that Respondent violated MRPC 1.15 by using certain client's funds being held in the attorney trust account to pay other clients and subsequently causing an overdraft of the attorney trust account. In doing so, Respondent also violated Maryland Rule 16-609(a), which states, "An attorney or law firm may not borrow or pledge any funds required by the Rules in this Chapter to be deposited in an attorney trust account. . . or use any funds for any unauthorized purpose." Additionally, pursuant to Maryland Rule 16-609(c), "[n]o funds from an attorney trust account shall be disbursed if the disbursement would create a negative balance with regard to an individual client matter or all client matters in the aggregate." Respondent's conduct further violates Maryland Code Annotated, Business Occupations and Professions § 10-306 which states that "[a] lawyer may not use trust money for any purpose other than the purpose for which the trust money is entrusted to the lawyer."Page 23

Respondent's use of client funds to pay other clients was clearly a misuse of the money Respondent was holding in trust for his clients. The facts demonstrate that this was a regular practice of Respondent. For example, as detailed in the facts above, in August 2011, Respondent paid his client Wankang $266.67 using funds deposited on behalf of two other clients. But for these deposits, Respondent would not have been able to pay Wankang. Eventually, Respondent's practice caused an overdraft in his trust account, in violation of bringing Respondent's conduct to the attention of Bar Counsel. Documentation provided to Bar Counsel by Respondent showed that his attorney trust account continually maintained a negative balance. Respondent admitted that client ledgers he had submitted to Bar Counsel indicating that he was properly maintaining his client's funds and maintaining an accurate account of said funds were false. Although Respondent testified that he corrected the overdraft as soon as he discovered its occurrence, the fact remains that the overdraft did occur, and that Respondent regularly used client's funds to pay other clients, in violation of MRPC 1.15, Maryland Rule 16-609, and Bus. and Occ. § 10-306.

Respondent failed to withdraw funds from his trust account only as he earned them as required by MRPC 1.15(c). For example, as detailed above, Respondent's invoice for his client Strand indicated that as of January 31, 2011, he had earned $141 of the $750 deposited in the trust account on her behalf, leaving a balance of $609. However, Respondent's total attorney trust account balance as of February 1, 2011 totaled $480.17, $128.83 less than the amount he was required to maintain on behalf of Strand, evidencing that Respondent withdrew Strand's funds prior to earning the same in violation of MRPC 1.15. Moreover, in the case of several clients, Respondent also failed to promptly withdraw funds as he became entitled to them as required by Maryland Rule 16-609(b)(2). Respondent represented in his client ledger for Strand that he withdrew $750 for attorney's fees on February 14, 2011. However, Respondent failed to make any withdrawals from his trust account on Strand's behalf on February 14, 2011 or at any time from February 2011 through August 2011. Respondent followed the same course of conduct with his other clients as well, namely: Wankang, Varticovski, Ardon, and Parra, in violation of Page 24Maryland Rule 16-609(b)(2).

For these reasons, this Court finds by clear and convincing evidence that Respondent violated Rule 1.15 by failing to appropriately safeguard his client's money and failing to appropriately maintain his client's funds in his attorney trust account.

Bowles escrow account

There is clear and convincing evidence that Respondent violated MRPC 1.15(a) by misappropriating funds in the Bowles escrow account. Respondent did so by issuing numerous checks to himself from the Bowles Estate, enumerated in the facts above, prior to authorization from the court or approval by interested parties. It is undisputed that Respondent knowingly took over $34,000 from the Bowles Estate from November 2005 through February 2009 beyond what had been approved by the Orphans' Court for him to take as personal representative commission and attorney's fees. Even assuming arguendo, that Respondent was approved, nunc pro tunc, by the three Orders of the Orphans' Court approving Respondent's Petitions for the earlier disbursements he made to himself in the total amount of $66,155.13, Respondent actually took a total of $68,760 as commission and fees, thereby taking an additional $2,604.87 over what the Court had authorized him to take as commission as fees. Thus, in either case, Respondent misappropriated funds from the Bowles escrow account in violation of MRPC 1.15(a). Respondent's use of the Bowles escrow account funds for such an unauthorized purpose is also a violation of Maryland Rule 16-609 and Maryland Code Annotated, Business Occupations and Professions § 10-306.

Respondent testified that it was his understanding that he could petition the court for fees only when the case was completed. Respondent also testified that he had the false impression that he could not call the Register of Wills and get information about petitioning for fees. However, Respondent presented no evidence demonstrating any attempts to contact the Register of Wills to see if a clerk was able to provide information or that he contacted one of his many colleagues to gain information about obtaining commission and fees as successor personal representative. Furthermore, despite his assertion that Page 25 he believed he could not file a petition prior the conclusion of the case, Respondent did file two petitions prior to filing his Third and Final Petition. For the reasons stated, the Court finds by clear and convincing evidence that Respondent violated MRPC 1.15 by using the funds in the Bowles account for the unauthorized purpose of paying himself commission and fees prior to approval.

MRPC 1.15(a); Md. Rule 16-607 (Commingling Funds)

There is clear and convincing evidence that Respondent violated Rule 1.15(a) (quoted above) by commingling his personal funds with his client's funds held in his attorney trust account and in the Bowles escrow account. In doing so, Respondent also violated Maryland Rule 16-607, which states, "An attorney or law firm may deposit in an attorney trust account only those funds required to be deposited in that account by Rule 16-604. . . ."

Respondent admitted to forty-four out of forty-five Requests for Admission from Bar Counsel. The only request Respondent declined to admit was that "[he] maintained [his] personal funds with the funds of [his] clients and/or third parties in [his] attorney trust account." However, the Court finds by clear and convincing evidence that Respondent did, in fact, maintain his personal funds with the personal funds of his clients in his attorney trust account. Respondent testified that he received a loan from his father, wired from his father's bank on three occasions: $5,000 on May 11, 2010, $3,000 on May 13, 2010, and $1,500 on October 6, 2010. Although Respondent asserted that the wiring of these funds into his trust account as opposed to his operating account was a mistake, the fact remains that these funds were in fact transferred into his trust account and commingled with client funds. Further, despite Respondent's assertion that the wiring into his attorney trust account was a mistake, Respondent did not immediately remove these funds once wired into the trust account. Furthermore, Respondent did not transfer these funds into this operating account, but instead transferred them into the Bowles escrow account. Additionally, the third allegedly "mistaken" transfer occurred five months after the first two transfers.

As a result of Respondent's multiple unauthorized Page 26disbursements to himself from the Bowles escrow account, Respondent had insufficient funds in the account to cover the actual expenses of the estate. As Respondent admitted both at trial and in his responses to Request for Admission, in order to have enough money to pay expenses of the Bowles estate, Respondent deposited his own personal funds, including monies from the loans from his father, into the Bowles Estate account. Therefore, Respondent commingled his personal funds with those held on behalf of his client as attorney for the Bowles Estate.

Respondent claimed that he did not know that he had to separate clients' funds held in escrow and that he did not have resources to help him learn to manage his accounts. However, Respondent's contention that he did not know this ethical rule does not affect the analysis as to whether Respondent violated this rule. Under Maryland law, "[c]laimed ignorance of ethical duties . . . is not a defense in disciplinary proceedings." Attorney Grievance Commission v. Awuah, 346 Md. 420, 435 (1997). Furthermore, Respondent has been an attorney for approximately thirty-five years. He is a member of the Sandy Spring Religious Society of Friends, which has several other members who are attorneys, including Judge Harrington, a retired Maryland judge, who testified on Respondent's behalf. Furthermore, Respondent's colleague, Christopher Flohr, former president of the Maryland Criminal Defense Attorney's Association, and an adjunct professor of law at the University of Maryland School of Law, testified that he teaches a course in law practice management. Certainly, Flohr could have been a valuable resource to Respondent in understanding how to properly maintain client funds. Respondent's assertion that he did not have the resources to learn how to manage his client's funds is simply false. Respondent was and is expected to know the ethical rules, including the requirement that he is required to properly maintain his clients' funds held when held in escrow.

For these reasons, this Court finds by clear and convincing evidence that Respondent violated Rule 1.15(a) by failing to hold property of his clients in his possession in connection with a representation separate from his own property.

MRPC 3.3(a)(1)

Rule 3.3(a)(1) provides:

(a) A lawyer shall not knowingly:Page 27

(1) make a false statement of fact or law to a tribunal or fail to correct a false statement of material fact or law previously made to the tribunal by the lawyer

There is clear and convincing evidence that Respondent made numerous false statements of material fact to the court and failed to correct previously made false statements Respondent made to the court, in violation of 3.3(a)(1). By his own admission, Respondent deliberately and knowingly fabricated or omitted information on all nine of the accounts he prepared, signed under oath, and filed with the court, including wrong dates, check numbers, amounts on checks, names of payees, and descriptions of alleged payments. Respondent also purposefully and knowingly failed to disclose all the disbursements he made to himself from the Bowles escrow account. In an effort to conceal the unauthorized disbursements to himself and his misappropriation of funds, Respondent made false statements to the court, claiming that he issued only two checks to himself: Check Number 115 in the amount of $15,834.37 and Check Number 1021 in the amount of $23,828.06, the exact amounts the Court authorized him to pay himself as and for personal representative commission and attorney's fees. However, Respondent never presented Check Number 115 for payment and Check Number 1021 was not written in the amount of $23,828.06, but for $30.25 to Nelson County, VA. Respondent knowingly misrepresented the payee and amount of Check Number 1021 to give the court the false impression that he was making proper and authorized disbursements to himself from the Bowles Estate, when, in fact, he had taken above and beyond what the court had authorized to pay himself as commission and attorney's fee. Respondent never corrected any of these false statements, even after becoming aware that Bar Counsel was conducting an investigation.

In addition to submitting accounts rife with fabrications and omissions, Respondent, again by his own admission, knowingly fabricated information in his Petitions for Attorney's Fees. In both his first and second Petitions, Respondent misrepresented the balance of the Bowles escrow account as higher than it actually was at the time he filed his Petitions. The account had a lesser amount than represented by Respondent due Page 28to the multiple unauthorized disbursements he had made to himself without approval from the Court. Even after being placed on notice by Bar Counsel of his unauthorized taking of monies from the Bowles escrow account, Respondent not only failed to take any corrective action to disclose the actual disbursements to himself, but filed a Third Petition for commission and fees with further misrepresentations. Respondent also continued to conceal the unauthorized disbursements he made to himself.

Respondent argues in mitigation that he did the work as provided for in his invoices, and was eventually approved for the monies he disbursed to himself prior to court approval. However, at the time he made the unauthorized disbursements to himself, he was uncertain as to whether the Court would approve them, particularly because his Petitions requested more than the statutory limit.

Respondent made numerous false statements to the court on both his accounts of the Bowles Estate and his Petitions for fees and failed to correct any of his misrepresentations and omissions. Respondent testified that he knew he had an obligation to notify the court that he took more disbursements than he stated in his accountings and that he failed to do so. Respondent asserted that this failure was due to a lack of self-confidence, a lack of experience, and an inability to reach out to others. However, Respondent has been a member of the Maryland Bar since 1988 and, since 1988, has had a responsibility to know and adhere to the Maryland Rules of Professional Conduct. While Respondent may have been inexperienced as a successor personal representative, he was not inexperienced as an attorney bound to the ethical rules. Further, Respondent had several colleagues at the Sandy Spring Religious Society of Friends he could have reached out to, in addition to others, such as Witness Christopher Flohr and colleagues.

For these reasons, the Court finds by clear and convincing evidence that Respondent violated MRPC 3.3(a)(1) by making and failing to correct false statements of material fact.

MRPC 8.4

Rule 8.4 provides:

It is professional misconduct for a lawyer to:

(a) violate or attempt to violate the Maryland Lawyers' Page 29Rules of Professional Conduct. . .;

. . .

(c) engage in conduct involving dishonesty, fraud, deceit or misrepresentation;

(d) engage in conduct that is prejudicial to the administration of justice. . . .

There is clear and convincing evidence that Respondent violated the Maryland Rules of Professional Conduct, knowingly made numerous misrepresentations to the court, knowingly misappropriated funds, and knowingly engaged in conduct prejudicial to the administration of justice, all in violation of MRPC 8.4. Because this Court has found that Respondent violated Rules 1.15 and 3.3 of the Maryland Rules of Professional Conduct, Respondent has consequently also violated Rule 8.4(a). Respondent violated 8.4(c) for the reasons stated in the MRPC 3.3(a)(1) analysis above.

As to Rule 8.4(d), the Court of Appeals has stated that an act prejudicial to the administration of justice is one that "tends to bring the legal profession into disrepute." Attorney Grievance Comm'n of Maryland v. Goodman, 426 Md. 115, 128, 43 A.3d 988, 995 (2012) (quoting Att'y Griev. Comm'n v. Rose, 391 Md. 101, 111, 892 A.2d 469, 475 (2006). In Goodman, the Court further noted that the Court of Appeals has long held that the commingling of personal and client funds is prejudicial to the administration of justice. Id. The Court of Appeals has also found that the intentional misappropriation of funds "erodes public confidence in the legal profession." Attorney Grievance Comm `n of Maryland v. Carithers, 421 Md. 28, 57, 25 A.3d 181, 198 (2011), reconsideration denied (Aug. 11, 2011). In the case sub judice, Respondent states that his actions did not cause financial harm to any of his clients. Regardless, his conduct, including the commingling and misappropriation of funds, is prejudicial to the administration of justice in that it tends to bring the legal profession into disrepute and may harm the public's confidence in the attorney-client relationship. Therefore, for the foregoing reasons, the Court finds by clear and convincing evidence that Respondent violated MRPC 8.4.

MitigationPage 30

This matter constitutes the first bar complaint against Respondent, who has been a lawyer for approximately thirty-five years. Based upon his time records and invoices, Respondent earned all fees he had received from his clients and his actions in this case never resulted in financial loss for any of his clients. Similarly, in the Bowles Estate matter, despite taking more commission and fees than the court approved, Respondent's actions did not result in receipt of fees or monies that he did not earn. Furthermore, the Bowles Estate was an complicated matter. Deputy Register Jane Gardner testified that in her nearly twelve years with the Orphans' Court, she had not seen a case like the Bowles Estate involving so many inappropriate disbursements without explanation by personal representative Michelle Allen. Respondent recovered $75,000 of misappropriated funds from Allen for the estate, obtained a $237,796.17 judgment against her for the estate, distributed $29,500 to the heirs, and with the help of Virginia counsel, acted in a foreign jurisdiction to acquire undeveloped rural property for the heirs appraised at $23,000. When closing out the Bowles estate, Respondent assigned the $237,796.17 judgment to the heirs in proportionate shares.

Since this matter began, Respondent has taken the following steps to correct his problematic office accounts and ensure compliance with the Rules of Professional Responsibility:

- Respondent requested that the Register of Wills remove him from the list of attorneys willing to be specially assigned to cases;

- On February 18, 2012, Respondent attended a Maryland State Bar Association continuing legal education seminar entitled "Hanging Out a Shingle" which discussed the appropriate method of using attorney escrow accounts;

- On November 12, 2012, Respondent attended a Maryland Criminal Defense Attorneys' Association seminar entitled "MCDAA Fall Extravaganza" which contained components on "Fee Issues and Illegal Funds" and "Typical Criminal Grievances and How To Avoid Them;"

- Respondent hired a licensed accountant to set up Quick Books on his office computer system with separate ledgers for both his attorney escrow account and office operating account. The same accountant now reviews Respondent's Quick Books system quarterly;Page 31

- Respondent met with Eric H. Singer, a Maryland attorney, who has agreed to meet monthly with Respondent, for a fee, to monitor his attorney escrow account records if this arrangement is appropriate as part of an overall disposition of this matter;

- Respondent reviewed his open cases and closed all remaining collections cases after determining that these cases were not economically viable;

- Respondent now requires sufficient retainers to support the costs likely to accrue in new cases he accepts;

- Respondent now maintains a running account ledger for all active cases with monies in his attorney escrow account, which must be added up and balanced each time money goes into or out of the trust account, in addition to maintaining a separate ledger sheet for each active case with monies in the trust account;

- Respondent underwent therapy with Adi Shmueli, Ph.D., a psychologist, and met bi-monthly with him from January 2012 through June 2012 to better understand the stresses and influences that contributed to his ethical lapses and to fashion therapeutic strategies and habits to avoid further lapses;

- Respondent has repeatedly counseled with elders of his Quaker Meeting in a specially requested group formally called a "clearness committee," confessing his errors as well as seeking support and guidance in remodeling his behavior. In addition, Respondent subsequently confessed his errors and sought support and guidance from former presiding clerks of his Quaker Meeting at a regular presiding clerks' dinner/meeting;

- Respondent has been actively involved in serving the public in a variety of community or professional activities, including:

* for at least twelve years with Fathers United, a self-help group for men going through a child custody or visitation contest, on a quarterly basis, as a guest attorney who fields questions from members;* for the last two years with Circle Treatment, an alcohol education and treatment center, on a quarterly basis, as a guest attorney explaining to Page 32group participants how the legal and administrative law systems work;

* for two terms of four years each in the last ten years with the Montgomery County Criminal Justice Coordinating Commission as a representative of private criminal defense attorneys;

* for the last ten years with Greater Sandy Spring Green Space, Inc., a land conservation group, as a member of the Board of Directors;

* in the late 1990s with the Olney Theater Center for the Performing Arts, as a member of a committee that established an endowment fund for the theater;

* for two terms of three years each with Friends House Retirement Community, Inc., and Friends Nursing Home, Inc., as a member of the Board of Trustees;

* with Sandy Spring Friends Meeting of the Religious Society of Friends, a Quaker meeting, as clerk of the Graveyard and Grounds Committee, as a member and later clerk of the Committee of Trustees, as assistant presiding clerk and as presiding clerk.

Conclusion

Wherefore, it is this 29th day of May, 2013, found by the Circuit Court for Montgomery County, for the reasons set forth herein, found that Respondent, Steven Gene Berry, has violated the following Maryland Rules of Professional Conduct: Rules 1.15, 3.3, and 8.4.

"This Court has original and complete jurisdiction over attorney discipline proceedings in Maryland." Attorney Grievance v. O'Leary, 433 Md. 2, 28, 69 A.3d 1121, 1136 (2013), quoting Attorney Grievance v. Chapman, 430 Md. 238, 273, 60 A.3d 25, 46 (2013). "[W]e accept the hearing judge's findings of fact as prima facie correct unless shown to be clearly Page 33 erroneous." Attorney Grievance v. Fader, 431 Md. 395, 426, 66 A.3d 18, 36 (2013), quoting Attorney Grievance v. Rand, 429 Md. 674, 712, 57 A.3d 976, 998 (2012). We review the hearing judge's conclusions of law de novo, pursuant to Rule 16-759(b)(1).[11]O'Leary, 433 Md. at 28, 69 A.3d at 1136.

Bar Counsel has filed no exceptions to Judge Salant's Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law. Berry filed a Motion to Exercise Revisory Power to Receive Additional Evidence, which we denied, as well as twenty-four pages of written exceptions and supplements to the Findings of Fact, which his counsel indicated at oral argument were abandoned. Two factual exceptions in which Berry had attempted to except himself from knowledge and wilfulness, were particularized at oral argument as immaterial, in addition to Page 34 being abandoned.[12]

We conclude that the hearing judge's factual findings were supported by clear and convincing evidence. We agree with Judge Salant's conclusions of law and find that they are supported by clear and convincing evidence.

Berry violated Rule 1.15(a) that "[a] lawyer shall hold property of clients or third persons that is in a lawyer's possession in connection with a representation separate from the lawyer's own property . . . maintained pursuant to Title 16, Chapter 600 of the Maryland Rules" by commingling personal funds with moneys in the Bowles Estate account and making unauthorized disbursements. Attorney Grievance v. Thompson, 376 Md. 500, 517-18, 830 A.2d 474, 484-85 (2003) (determining that because the personal representative took Page 35 commissions prior to approval from the Orphans' Court and, therefore, improperly handled estate distributions, he violated Rule 1.15(a)). Berry also violated Rule 1.15(a), robbing Peter to pay Paul, by using client funds to pay other clients or fund their cases, running a negative balance in his attorney trust account and depositing personal funds into the account in violation of Md. Rules 16-607 and 16-609, as well as Section 10-306 of the Business Occupations and Professions Article of the Maryland Code. Attorney Grievance v. Thomas, 409 Md. 121, 150-52, 973 A.2d 185, 202-03 (2009).

Berry also violated Rule 3.3(a)(1), requiring that, "[a] lawyer shall not knowingly make a false statement of fact or law to a tribunal or fail to correct a false statement of material fact or law previously made to the tribunal by the lawyer." Berry, in three Petitions for Allowance of Interim Personal Representative Commission and Interim Attorney's Fees, filed over seven years with the Orphans' Court, failed to disclose the numerous unauthorized payments he made to himself. Additionally, Berry filed nine Accounts of Successor Personal Representative with the Orphans' Court, in which he not only omitted check numbers, but mis-identified payees on checks and falsified amounts, as well as balances to reconcile each account. In his Second Account, for example, Berry attested that check number 134 was issued to the "U.S. Postal Service" for $11.16, when, in reality check number 134 had been written by Berry to himself for $2,000. Berry's deceit in concealing payments to himself from the Bowles Estate is present in each of the accounts, which he never corrected, all in violation of Rule 3.3. Attorney Grievance Comm'n v. Williams, 335 Md. 458, 471, 644 A.2d 490, 496 (1994) (determining that attorney serving as personal representative violated Rule 3.3 where Page 36 he "reported an inaccurate figure as the balance in the decedent's savings account and failed to file an amended petition correcting that error").

Berry violated Rules 8.4(c) by "engag[ing] in conduct involving dishonesty, fraud, deceit or misrepresentation" and 8.4(d) by "engag[ing] in conduct that is prejudicial to the administration of justice." Berry made false statements to the Orphans' Court in twelve separate filings, including three fee petitions and nine accounts. Attorney Grievance v. Steinberg, 395 Md. 337, 369, 910 A.2d 429, 448 (2006) (determining that knowingly false statements made by an attorney in a motion in a bankruptcy proceeding constituted violations of Rules 3.3, 8.4(c) and (d)). He took funds from the Bowles Estate account without court authorization. Attorney Grievance v. Sullivan, 369 Md. 650, 655-56, 801 A.2d 1077, 1080 (2002) (concluding that the attorney's mishandling of an estate account, including taking of funds without court approval, while serving as personal representative reflected "adversely on his honesty, trustworthiness and fitness as an attorney" and "was conduct prejudicial to the administration of justice" in violation of Rules 8.4(c) and (d)). Berry also misused client funds in his attorney trust account. See Attorney Grievance v. Gallagher, 371 Md. 673, 712-13, 810 A.2d 996, 1019-20 (2002) (determining that the attorney violated Rules 8.4(c) and (d) by his intentional deceitful conduct, failing to hold his client's funds in trust and misleading the client regarding the use of the funds).

Bar Counsel recommends disbarment, as "[t]his instant case involves both misappropriation of client funds and repeated misrepresentations to a tribunal by Respondent" while Berry recommends an indefinite suspension with the right to apply for reinstatement Page 37 after one year.[13]

In imposing sanctions, we will consider "the nature of the ethical duties violated in light of any aggravating or mitigating circumstances." Attorney Grievance v. Paul, 423 Md. 268, 284, 31 A.3d 512, 522 (2011). With regard to aggravating factors, we look to Section 9.22 of the American Bar Association Standards for Imposing Lawyer Sanctions (1992) including:

(a) prior disciplinary offenses;(b) dishonest or selfish motive;

(c) a pattern of misconduct;

(d) multiple offenses;

(e) bad faith obstruction of the disciplinary proceeding by intentionally failing to comply with rules or orders of the disciplinary agency;

(f) submission of false evidence, false statements, or other deceptive practices during the disciplinary process;

(g) refusal to acknowledge wrongful nature of conduct;

(h) vulnerability of victim;

(i) substantial experience in the practice of law;

(j) indifference to making restitution.

Attorney Grievance v. Bleecker, 414 Md. 147, 176-77, 994 A.2d 928, 945-46 (2010). In this case, factors (b), (c), (d) and (i) are implicated.

Of vital importance in this case is factor (b), "dishonest or selfish motive." Berry demonstrated an ongoing pattern of deceitful conduct with the Bowles Estate account, submitting multiple Petitions for commissions and fees with false account balances and Page 38 without disclosing his unauthorized disbursements to himself, as well as submitting nine fraudulent Accounts to conceal his unauthorized withdrawals, thereby implicating factor (b). Attorney Grievance v. Seltzer, 424 Md. 94, 117, 34 A.3d 498, 512 (2011).

Factor (c), "a pattern of misconduct," is also implicated. Berry repeatedly engaged in deceitful actions throughout the seven years he served as successor personal representative of the Estate. He disbursed more than twenty unauthorized checks to himself and submitted three misleading Petitions and nine fraudulent Accounts to the court, rife with falsifications, to conceal the disbursements. Attorney Grievance v. Penn, 431 Md. 320, 345, 65 A.3d 125, 140(2013).

Factor (d), "multiple offenses," is implicated by numerous violations of the Rules. Id., citing Bleecker, 414 Md. at 177-78, 994 A.2d at 946. Berry committed numerous violations of the Rules, not only as a result of his actions as successor personal representative of the Bowles Estate account, but also because he commingled personal and client moneys in his attorney trust account. Attorney Grievance v. Fader, 431 Md. 395, 437, 66 A.3d 18, 43 (2013).

Finally, factor (i) is implicated because Berry had been a member of the Maryland Bar since 1988, demonstrating that he had "substantial experience in the practice of law." Id.

We also consider mitigation to determine the appropriate sanction. Paul, 423 Md. at 284, 31 A.3d at 522. Under Section 9.32 of the American Bar Association Standards for Imposing Lawyer Sanctions (1992), mitigating factors include:

Absence of a prior disciplinary record; absence of a dishonest orPage 39 selfish motive; personal or emotional problems; timely good faith efforts to make restitution or to rectify consequences of misconduct; full and free disclosure to disciplinary board or cooperative attitude toward proceedings; inexperience in the practice of law; character or reputation; physical or mental disability or impairment; delay in disciplinary proceedings; interim rehabilitation; imposition of other penalties or sanctions; remorse; and finally; remoteness of prior offenses.

Penn, 431 Md. at 343-44, 65 A.3d at 139, quoting Attorney Grievance v. Brown, 426 Md. 298, 326, 44 A.3d 344, 361 (2012). Judge Salant found, in mitigation, that Berry had no prior grievances; that "[b]ased upon his time records and invoices, Respondent earned all fees he had received from his clients"; that the handling of the Bowles Estate was complex; that Berry recovered $75,000 of misappropriated funds and a $237,796.17 judgment for the Estate, from which $29,500 was distributed to the heirs, and that he worked, with the assistance of local counsel, to acquire property for the heirs appraised at $23,000. Judge Salant also found that Berry requested removal of his name from the Register of Wills' list of available attorneys; attended seminars regarding appropriate use of escrow accounts and fee issues; closed existing collections cases that were not economically viable; hired a licensed accountant to set up and regularly review a new office accounting system; met with an attorney to monitor his escrow accounts; and altered his existing accounting practice. Judge Salant also found that Berry underwent therapy, counseled with elders in his Quaker community, and was actively involved in public service.

"[D]isbarment is warranted where a lawyer acts dishonestly because dishonest conduct is `beyond excuse': `Unlike matters relating to competency, diligence and the like, intentional Page 40 dishonest conduct is closely entwined with the most important matters of basic character to such a degree as to make intentional dishonest conduct by a lawyer almost beyond excuse.'" Penn, 431 Md. at 345, 65 A.3d at 140, citing Attorney Grievance v. Vanderlinde, 364 Md. 376, 418, 773 A.2d 463, 488 (2001); see also Attorney Grievance v. Nussbaum, 401 Md. 612, 643-44, 934 A.2d 1, 19 (2007), citing Attorney Grievance v. Cherry-Mahoi, 388 Md. 124, 161, 879 A.2d 58, 81 (2005); Sullivan, 369 Md. at 655-56, 801 A.2d at 1080; Attorney Grievance Comm'n v. Boehm, 293 Md. 476, 481, 446 A.2d 52, 54 (1982). Here, Berry intentionally and knowingly lied to the Orphans' Court over and over again in twelve different petitions and accounts during a seven year period. His conduct is beyond justification or rationalization.

Berry, however, proffers that an indefinite suspension is appropriate, relying upon Attorney Grievance v. Pleshaw, 418 Md. 334, 15 A.3d 777 (2011),[14]Attorney Grievance Comm `n v. Owrutsky, 322 Md. 334, 587 A.2d 511 (1991), Attorney Grievance v. Kendrick, 403 Md. 489, 943 A.2d 1173 (2008), Attorney Grievance v. Seiden, 373 Md. 409, 818 A.2d 1108 (2003), Attorney Grievance v. Tun, 428 Md. 235, 51 A.3d 565 (2012); Attorney Grievance v. DiCicco, 369 Md. 662, 802 A.2d 1014 (2002) and Attorney Grievance v. Jeter, 365 Md. 279, 778 A.2d 390 (2001). In Owrutsky, 322 Md. at 355-56, 587 A.2d at 521, we determined that the attorney's conduct, although "perilously close to misappropriation of Page 41 funds" reflected "carelessness and neglect in the handling of these estates and trusts", and therefore, warranted a sanction of three years' suspension. In Kendrick, 403 Md. at 522, 943 A.2d at 1191-92, we imposed an indefinite suspension, because the attorney's conduct was "not due to greed or dishonesty, but rather due to obstinateness and incompetence in probate matters." Likewise, in Seiden, 373 Md. at 423-25, 818 A.2d at 1116-17, Tun, 428 Md. at 248, 51 A.3d at 573, DiCicco, 369 Md. at 687-88, 802 A.2d at 1028, and Jeter, 365 Md. at 293-94, 778 A.2d at 398, we determined that indefinite suspensions were appropriate because the attorneys' conduct was negligent, not intentionally dishonest.

Berry acted dishonestly over a seven year period repeatedly, in twelve separate filings. He took Estate money for which he had no authorization from the Orphans' Court and concealed disbursements to himself. Accordingly, we disbarred Steven Gene Berry.

(a) Commencement of disciplinary or remedial action. (1)

Upon approval or direction of Commission. Upon approval or direction of the Commission, Bar Counsel shall file a Petition for Disciplinary or Remedial Action in the Court of Appeals.

(a) A lawyer shall not knowingly:

(1) make a false statement of fact or law to a tribunal or fail to correct a false statement of material fact or law previously made to the tribunal by the lawyer;

It is professional misconduct for a lawyer to:

* * *

(b) commit a criminal act that reflects adversely on the lawyer's honesty, trustworthiness or fitness as a lawyer in other respects;

(c) engage in conduct involving dishonesty, fraud, deceit or misrepresentation;

(d) engage in conduct that is prejudicial to the administration of justice;

Bar Counsel's initial pleading included a charged violation of Rule 8.4(b), which he subsequently apparently abandoned. Although the hearing judge drew conclusions of law relative to Rule 8.4(a), Rule 8.4(a) was not specifically charged in the Petition, so we will not consider it further. Attorney Grievance v. Sapero, 400 Md. 461, 487, 929 A.2d 483, 498 (2007) ("[A]n attorney may not be found guilty of violating a Rule of Professional Conduct unless that Rule is charged in the Petition For Disciplinary or Remedial Action.").

(a) A lawyer shall hold property of clients or third persons that is in a lawyer's possession in connection with a representation separate from the lawyer's own property. Funds shall be kept in a separate account maintained pursuant to Title 16, Chapter 600 of the Maryland Rules, and records shall be created and maintained in accordance with the Rules in that Chapter. Other property shall be identified specifically as such and appropriately safeguarded, and records of its receipt and distribution shall be created and maintained. Complete records of the account funds and of other property shall be kept by the lawyer and shall be preserved for a period of at least five years after the date the record was created.

A lawyer may not use trust money for any purpose other than the purpose for which the trust money is entrusted to the lawyer.

(b) Attorney trust accounts. - A person who willfully violates any provision of Subtitle 3, Part I of this title, except for the requirement that a lawyer deposit trust moneys in an attorney trust account for charitable purposes under § 10-303 of this title, is guilty of a misdemeanor and on conviction is subject to a fine not exceeding $5,000 or imprisonment not exceeding 5 years or both.

a. General Prohibition. An attorney or law firm may deposit in an attorney trust account only those funds required to be deposited in that account by Rule 16-604 or permitted to be so deposited by section b. of this Rule.

a. Generally. An attorney or law firm may not borrow or pledge any funds required by the Rules in this Chapter to be deposited in an attorney trust account, obtain any remuneration from the financial institution for depositing any funds in the account, or use any funds for any unauthorized purpose.

b. No cash disbursements. An instrument drawn on an attorney trust account may not be drawn payable to cash or to bearer, and no cash withdrawal may be made from an automated teller machine or by any other method. . . .

(a) Generally. The hearing of a disciplinary or remedial action is governed by the rules of evidence and procedure applicable to a court trial in a civil action tried in a circuit court. Unless extended by the Court of Appeals, the hearing shall be completed within 120 days after service on the respondent of the order designating a judge. Before the conclusion of the hearing, the judge may permit any complainant to testify, subject to cross-examination, regarding the effect of the alleged misconduct. A respondent attorney may offer, or the judge may inquire regarding, evidence otherwise admissible of any remedial action undertaken relevant to the allegations. Bar Counsel may respond to any evidence of remedial action.

(b) Burdens of proof. The petitioner has the burden of proving the averments of the petition by clear and convincing evidence. A respondent who asserts an affirmative defense or a matter of mitigation or extenuation has the burden of proving the defense or matter by a preponderance of the evidence.

(c) Findings and conclusions. The judge shall prepare and file or dictate into the record a statement of the judge's findings of fact, including findings as to any evidence regarding remedial action, and conclusions of law. If dictated into the record, the statement shall be promptly transcribed. Unless the time is extended by the Court of Appeals, the written or transcribed statement shall be filed with the clerk responsible for the record no later than 45 days after the conclusion of the hearing. The clerk shall mail a copy of the statement to each party.

(d) Transcript. The petitioner shall cause a transcript of the hearing to be prepared and included in the record.

(e) Transmittal of record. Unless a different time is ordered by the Court of Appeals, the clerk shall transmit the record to the Court of Appeals within 15 days after the statement of findings and conclusions is filed.

(b) Review by Court of Appeals. (1) Conclusions of law. The Court of Appeals shall review de novo the circuit court judge's conclusions of law.

(2) Findings of fact. (A) If no exceptions are filed. If no exceptions are filed, the Court may treat the findings of fact as established for the purpose of determining appropriate sanctions, if any.

(B) If exceptions are filed. If exceptions are filed, the Court of Appeals shall determine whether the findings of fact have been proven by the requisite standard of proof set out in Rule 16-757 (b). The Court may confine its review to the findings of fact challenged by the exceptions. The Court shall give due regard to the opportunity of the hearing judge to assess the credibility of witnesses.

There are two factual exceptions that I will argue today, which I will let the Court know now, I believe are not material to the outcome of the situation, they're more of refining certain factual things . . . there are nothing in the exceptions that go to whether any of these rules were or not violated because they were.

* * *

The first one is the assertion that he didn't have the resources to learn how to manage his clients' funds. . . . It wasn't a lack of resources. It was his own ineptitude. He understood that resources existed to help him out. He didn't access them. He failed to reach out. . . . The other one . . . which said that the client was uncertain about whether the court was going to give approval for his fee petitions . . . what I am arguing to the Court is there was no lack of certainty on Mr. Berry's part as to whether the court would approve these fee petitions. It was quite simply, again, a failure of his to do what he was supposed to do and what he knew the law required, which was to file the petitions first, before you take the fees.

- Decided on .

Page 17

Page 17