The Lawyer's Lawyer

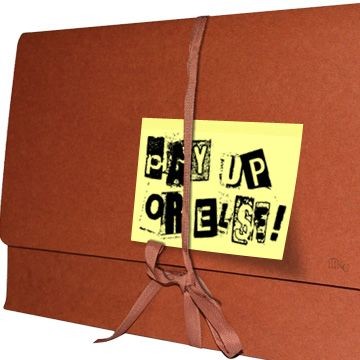

Holding Files for Ransom

Q. After ten months of discovery in a complex civil case, my client fired me for "taking too long" and refused to pay her bill. Now, her new lawyer has asked me for the file. May I keep it until I get paid?

A. Even in states that expressly permit you to hold files for ransom, you may live to regret it.

Having worked hard to earn your fee, you are legally entitled to assert an attorney's lien on the case. Historically, states recognized two types of attorney's liens:

1. The "Retaining Lien" - until your client pays her bill, you have all of the client's property in your possession; and

2. The "Charging Lien" - often applied in contingency cases, many state statutes would entitle you to a portion of a monetary judgment resulting from your work.

Although the charging lien may not apply here, a retaining lien would enable you to hold the client's file hostage until she pays all reasonable attorney's fees earned in the case. This seems only fair and would prevent a client from benefiting from your services while skipping out on your bill.

But Bar Counsel doesn't care whether you get paid. Even where you have a right to retain the file until the client pays, asserting this retaining lien may violate the Rules of Professional Conduct. Under Rule 1.16(d), when representation terminates, "an attorney shall take steps to the extent reasonably practicable to protect a client's interests, such as ... surrendering papers and property to which the client is entitled." This is particularly true for time-sensitive litigation where an inability to access key evidence may undermine the client's case.

Even if you have a valid lien, asserting it is risky. In my experience, lawyers who deny their former clients access to their files are challenging them, or their new counsel, to file grievances. When they complain to authorities, the same courts that reaffirm lawyers' rights to assert retaining liens are quick to punish them for doing so. Quite often, these courts will find fault with lawyers' billing practices, invalidate their liens, and sanction them for improperly withholding client property. See, e.g., Attorney Grievance Comm'n v. Rand, 445 Md. 581, 128 A.3d 107 (2015).

In suspending an attorney from the practice of law, one court found that the "mere existence of a legal right does not entitle a lawyer to stand on that right if ethical considerations require that he forego it." Attorney Grievance Comm'n v. Sheridan, 357 Md. 1, 35, 741 A.2d 1143 (1999). Showing greater concern for the client's rights than for your right to fair compensation, the court would "not countenance in a disciplinary proceeding such a self-help argument for vigilante lawyers who decide to take disputes over attorney's fees into their own hands." Id.

Interesting contradiction. Lawyers have a legal right to retain the file, but are rebuked as "vigilantes" when they exercise it.

Admonishing lawyers to place their clients' interests first, disciplinary boards often prosecute those who don't: "If a client needs papers solely in the possession of the lawyer following termination of the attorney-client relationship," one prosecutor warns that "the assertion of a retaining lien will not always trump the overriding obligation to protect the interests of the client." Lydia E. Lawless, An Attorney's Right to Assert a Retaining Lien: Possession is But a Small Fraction of the Law, The Maryland Litigator at 14 (May 2016) (emphasis added). If this really is an "overriding obligation," it is apparent that the duty to return the file will always trump the right to retain it.